Jason highlights the connection between ancient traditions of military mountain activity and twentieth-century mountaineering.

Greek and Roman history writing is packed with descriptions of military activity in the mountains: it’s probably the category of mountain description that survives in the biggest volume from the ancient Mediterranean world, especially from the Roman empire. In classical Greece the dominance of heavily armed hoplite warfare meant that fighting usually took place on the plains, but for later centuries, especially for Rome’s combat against foreign enemies on the edges of their expanding empire, there are countless accounts of mountain combat.

It is tempting at first sight to think that these accounts have very little to do with modern traditions of writing about mountains, which we tend to assume are dominated by aesthetic responses and by the association between mountains and leisure. But actually when you look more closely it becomes clear that a large proportion of modern mountain writing, especially in the 20th century, has a heavily military character which is very much in the ancient tradition of writing about mountain conquest.

That goes especially for the major Himalayan expeditions of the mid 20th century, many of which were dominated by former soldiers. For example, John Hunt, leader of the successful 1953 Everest expedition, had spent some of the war as chief instructor at the Mountain Warfare School in Braemar before commanding a battalion on active service in Italy; he spoke later about his ‘military pragmatism’ as one of his main contributions (The Guardian, 9 November 1998) and his account of the expedition is heavily marked by that military experience, with its emphasis on efficiency and organisation, and also by imperial and nationalist sentiment, but with almost no mention of the beauty or sublimity of the mountain scenery.

HANNIBAL AND MAURICE HERZOG

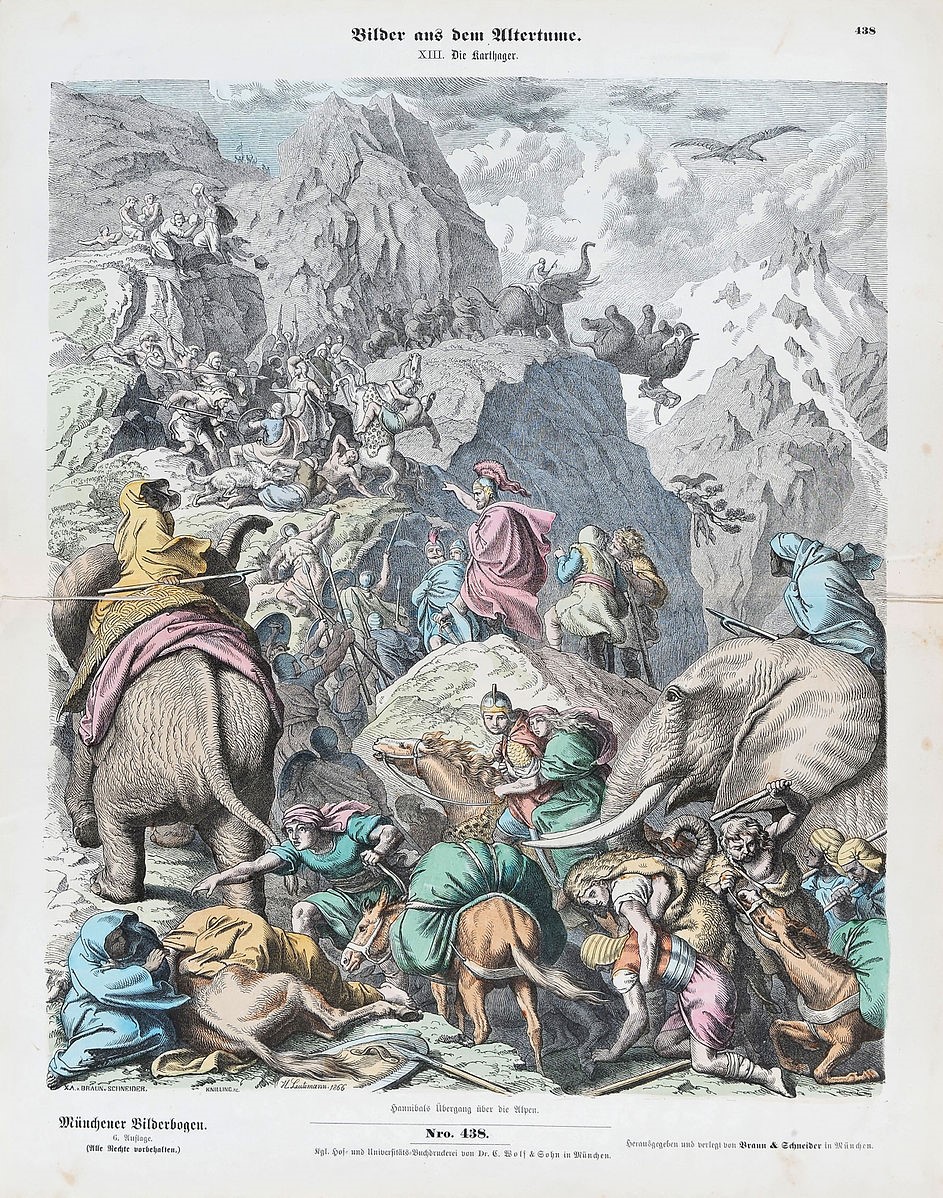

One of the things those accounts share with ancient writing about mountain warfare (perhaps not surprisingly) is their emphasis on painstaking, tactile engagement with mountain terrain, especially its impact on the feet. Perhaps most famous of all is Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, the precursor to his invasion of Italy. One of the historians who tells that story is Polybius, writing in the second century BCE. He is interested in particular in the soldiers’ physical contact with the ground of the Alps. On their descent, for example, they find the snow hard to walk through:

new snow had recently fallen on top of the already existing snow which had survived from the previous winter, and it so happened this this was easy to slip through, both because it was freshly fallen and so soft, and because it was not yet deep. But whenever they had trodden through it and set foot on the congealed snow underneath they no longer sunk into it, but slipped along with both feet, as happens to those who travel over ground coated with mud. But what followed on from this was even more difficult. For the men, being unable to pierce the layer of snow underneath, whenever they fell and tried to get a grip with their knees or hands in order to stand up, then they slipped all the more precisely because they were pressing down, the ground being exceptionally steep. (Polybius 3.55.1-4).

Modern writing about mountains too often has an obsession with the concrete challenges of the terrain. Maurice Herzog’s Annapurna, first published in 1951, is a good example. Herzog does sometimes mention the beauty and magnificence of the mountains (more often than Hunt), and feelings of happiness and exhilaration, especially at moments of relaxation, but for long sections what preoccupies him instead is the detail of the route and the terrain and the decisions he and his companions have to take to get through it, sometimes literally step by step. The passage where he describes the final struggle to reach the summit is a typical example:

The couloir up the rocks though steep was feasible. The sky was a deep sapphire blue. With a great effort we edged over to the right, avoiding the rocks. We preferred to keep to the snow on account of our crampons and it was not long before we set foot in the couloir…Fortunately the snow was hard, and by kicking steps we were able to manage, thanks to our crampons. A false move would have been fatal…A slight detour to the left, a few more steps—the summit ridge came gradually nearer—a few rocks to avoid. We dragged ourselves up.

Of course this is different from the descriptions of Hannibal. Herzog’s account is intensely personal, full of anxiety and exhilaration. And yet Herzog’s moments of personal reminiscence are often overshadowed by painstaking descriptions of his engagement with the mountain terrain as a real, concrete presence, to be grappled with and overcome—in other words precisely the kind of language we have seen in Polybius. The prevalence of that material, stretching out before us for pages and pages on end, articulates the ambition and scale of the expedition Herzog is a part of.

The quasi-military character of that expedition is also impossible to miss: the imagery of ‘assault’, ‘victory’, ‘conquest’ recurs over and over again. Take for example the first page of the preface, written by Lucien Devies, President of the ‘Comité de l’Himalaya’ and of the ‘Fédération Française de la Montagne’: ‘the conquest of Annapurna…With this victory…Victory in the Himalaya is a collective victory… the victory of the whole party was also, and above all, the victory of its leader’.

ARMY BOOTS AND BLISTERS

Looking back on it now—I had never really noticed it before—I can see that my own early experience of mountains was a military one too. Like many English private-school students in the 1980s I had to spend one afternoon a week in my school cadet force. I managed to endure the hideousness of drill and boot polishing for a year and then escaped into the ‘Adventure Training’ section to do rock climbing and canoeing, but even there it was impossible to get away from the faint military hangover. Several times a year we were bused off to Wales and sent off to go and walk in the hills. I am grateful for it now, but I don’t think it was ever very pleasant. I suppose we must have admired the views sometimes, but I don’t remember it if so. In my memory it is always raining. Most of all I remember the kit: badly fitting army boots and old military rations. I remember coming down off one hill at the end of 16 hours of walking (having slept on the summit of Snowdon to get an early start): a fourteen-year old boy, trying not to cry, limping along behind the others with blisters the size of jam-jar lids on my feet. I would have sympathised with Hannibal and his men then. Maybe those ancient accounts of Greek and Roman armies are not so far away from types of mountain experience which still have a hold over us today.

Illustrations: Front covers of John Hunt, The Ascent of Everest (2013 50th-anniversary edition; first published 1953) and Maurice Herzog, Annapurna (1997 edition; first published 1951) and Heinrich Leutemann, Die Karthager – Hannibals Übergang über die Alpen, 1866.