Jason explores a few ancient examples of seeing beauty in mountains.

ANCIENT AND MODERN RESPONSES

One of the goals of this project is to look across the watershed of the late 18th and early 19th centuries to give fresh attention to early modern, medieval and especially classical responses to mountains.

When you do that you see lots of differences: some aspects of ancient engagement with mountains are entirely alien to anything we are familiar with. But you also see lots of continuities and similarities, surprisingly so for anyone who has grown up with the standard view that our own way of interacting with mountains is an invention of the romantic period, and a distinctive feature of our modernity.

There are some obvious questions to start with. We can look at mountain climbing: the ancient Greeks and Romans went up mountains surprisingly regularly, even if not for leisure purposes—more on that in a later post.

We can look at habits of viewing from mountain summits: again, that was surprisingly widespread in ancient culture, as Irene de Jong’s recent work has shown (she refers to the motif of viewing from the summit as oroskopia, from the Greek word for mountain, oros).

We can also look at aesthetic responses. There are responses very much like modern ideas of the sublime in ancient descriptions of mountains (more on that in later posts and publications).

BEAUTIFUL MOUNTAINS IN THE ANCIENT WORLD?

But what I want to look at here is the habit of describing mountains as beautiful. Do we find anything like that in ancient Mediterranean culture? That question matters partly because one of the stereotypes of medieval and ancient culture is that they viewed mountains as places of gloom and ugliness.

It is undeniable that extended set-piece descriptions of mountains were much rarer in ancient Greek and Roman culture than they are for us (and the same goes for visual depictions). Most often rhetorical landscape descriptions were of meadows and groves: the locus amoenus (‘pleasant place’) tradition which was central to ancient pastoral. The rhetorical theorist Pseudo-Hermogenes tells us that ‘there have even been encomia of plants and mountains and rivers’, but that word ‘even’ suggests that we should not expect to see them too often.

But when we look more closely we see plenty of exceptions which suggest that a beautiful mountain was absolutely conceivable. When orators gave speeches in praise of the cities they were visiting, they would sometimes mention the city’s mountains. Menander Rhetor in one of his works giving instructions for speech-making includes mountains along with plains, rivers and harbours as standard subjects. There are several examples in the work of the orator Dio Chrysostom, who lived in Asia Minor in the late first and early second century CE: he praises the mountains around the city of Tarsus (33.2) and later in the same speech claims that the beauty of Mt Ida was an asset for the city of Troy (33.20). In another speech he praises the beauty of the mountains surrounding the city of Celaenae in Phrygia (35.13).

PLINY THE YOUNGER

In a rather different context, Pliny the Younger writes in one of his letters (5.6) to his friend Domitius Apollinaris inviting him to stay in his Tuscan villa. The appearance of the region, he boasts, is

most beautiful. Imagine to yourself a huge amphitheatre, of the kind that only nature could create. A broad and extensive plain is surrounded by mountains; the mountains on their summits have tall and ancient forests. There is abundant and varied hunting there. From there, woods ready for felling stretch down together with the mountain slopes. Interspersed between these are rich and earthy hills…which are not inferior to the most level plains in fertility…You would take great pleasure, if you could view this layout of the region from the mountain. For you would think you were looking not at the earth, but at a view painted to the highest level of beauty; such is the variety, such is the arrangement that wherever the eyes fall they will be refreshed.

The villa is artfully constructed to give different views from different angles, and the mountain view is part of that design: ‘At the end of the cloister is a bedroom cut out from the cloister itself, which looks over the hippodrome, the vineyards, and the mountains’.

This passage anticipates to a remarkable degree many of the common motifs of modern landscape appreciation: beautiful mountains as part of a crafted backdrop combining human cultivation with the spontaneity of nature, assessed by the criteria of landscape painting, all in a way that seems to guarantee the good taste and social status of the letter writer.

MOUNTAINS AND CITIES

Clearly then the idea of mountains as beautiful, as objects of aesthetic admiration, was perfectly conceivable and even commonplace in some contexts. And yet it is also striking that all of these examples have one thing in common and that is the way in which the mountains they depict are in urban contexts, or at any rate stand as backdrops to human habitation. There are modern parallels for that, of course, but mountain beauty for us can also be found outside civilization.

We see the same pattern in many of the best mountain images we have from ancient art, as in the wall painting from Pompeii below, from the house of Lucretius Fronto:

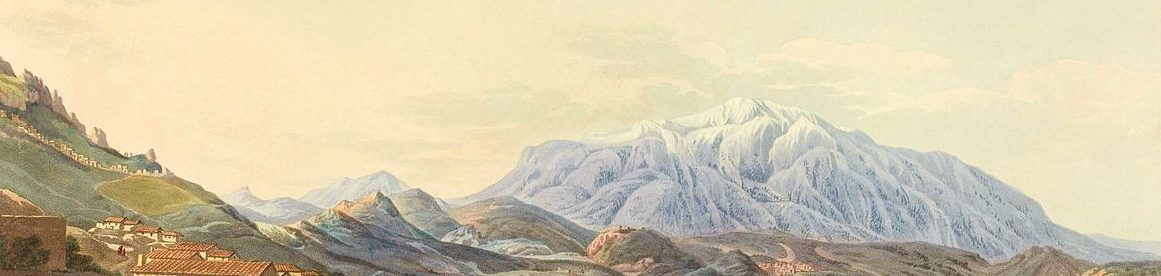

The mountains in the image are unidentified. But of course the inhabitants of Pompeii were themselves entirely familiar with the idea of mountains as backgrounds to the fabric of the city. Looking north from the forum they would see Mt Vesuvius (seen at the top of this post), and to the south Monte Faito.

Mountains could be beautiful to ancient viewers, then. But it looks as though there were cultural differences too, especially in the way in which the relationship between landscape beauty and wilderness was understood…

Illustrations: Vesuvius from Pompeii, CC BY-SA 2.0; Casa di Marco Lucrezio Frontone, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The question of landscape appreciation came up during an A-level lesson recently, so this is very timely.

Something that strikes me about Pliny’s letter is how his idea of beauty is tied to usefulness – are the woods beautiful because they are ready for felling and provide good hunting, the hills because they are unexpectedly fertile. Even the mountains are described in relation to architecture.

Aside from beauty as an association with a particular god’s favoured location, or mountains as a backdrop to a city, are there any good examples that match with the Romantic idea of “the sublime”?

Hi Stephen–thanks for this. Those are interesting questions… I hadn’t noticed the emphasis on usefulness before in the Pliny passage, but I think you are probably right about that–and that’s perhaps all part of the way in which mountains are more likely to be described as beautiful in ancient texts if they are marked in some way by human culture. As for the sublime: that’s a huge question, and I think it’s one we will have to come back to in future posts!–but basically, yes, I think there are lots of aspects of ancient mountain description that are much closer to the Romantic ‘sublime’ than has generally been assumed–a text like the Pseudo-Virgilian Aetna is an obvious place to look–even if it is never quite articulated in the same way or in such personal terms…

When Pliny the Younger wrote of his “huge amphitheatre, of the kind that only nature could create,” he probably had in mind an ekphrasis from Virgil, and more generally the Roman tradition of fresco painting as explicitly theatrical decoration for domestic interiors. Pliny’s elaborate invitation to Domitius Apollinaris plays artfully within a shared visual and literary culture.

It was Vitruvius who had divided the suitable subject matter for fresco into three categories corresponding to genres of theatrical backdrop: tragic, comedic, and satyric. What we would call “landscape,” corresponds to the satyric. Vitruvius’s list of exemplary topics includes “harbors, headlands, shores, rivers, springs, straits, temples [fana], groves, mountains, cattle, shepherds;” all of them, according to Vitruvius, well suited to the panoramic decoration of long covered porticoes (De arch. 7.5.1-2. Many fragments of all three genres of this nearly lost art, such as the wall fragment with a small framed picture painted into it (above), are extant in the ruins at Herculaneum and Pompeii. The depicted house is shaped like a Roman proscenium theater and would have been understood as a backdrop for comedy.

So, yes, to Jason’s broader points: Romans found mountains beautiful enough to decorate their interiors with pictures of them; moreover, the habit of picturesque description—describing nature as if it were art—long predates eighteenth century attempts to theorize the practice.

Pliny’s amphitheatre more specifically alludes to Virgil’s ekphrasis of the steep, U-shaped cliffs sheltering the Carthaginian harbor: “silvis scaena coruscis,” a theatrical backdrop of shimmering woods (Aen 1.157-73). Virgil had in turn learned from Homer’s mysterious tension between the natural and the artifactual in the Phorcys harbor ekphrasis at Od. I3.96-112. I discuss in some detail Virgil’s harbor and some implications for later landscape aesthetics in The Poetics of Description: Imagined Places in European Literature, Palgrave Macmillan (2006), 69-95.

Thanks Jan–very interesting to see these comments: that’s very helpful.