Jason considers both ancient and modern responses to one of Greece’s most enigmatic mountains.

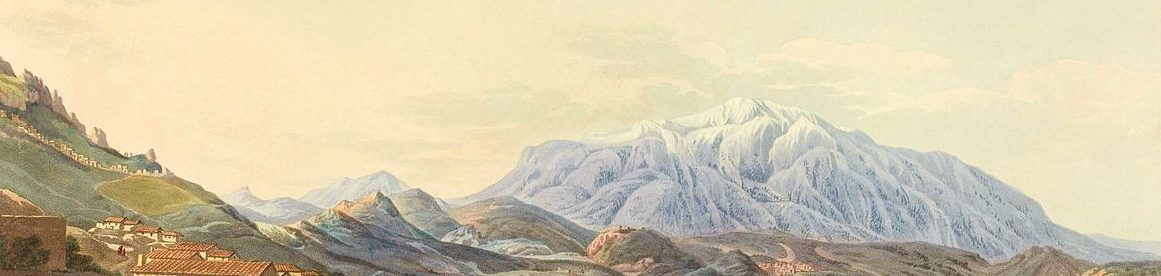

One of the projects I have been working on for a while now is a biography of Mt Olympus. Olympus is the highest mountain in mainland Greece, at just under 3000 metres. It’s a complex mountain, with multiple peaks and steep cliffs beneath the highest summits.

It had a central role in Greek mythology. In the Homeric poems and for centuries later Olympus was the home of the gods: the Iliad and the Odyssey describe the divine palaces and banqueting halls on its summit.

But in some ways it’s an unusual mountain in the responses it has provoked in both ancient and modern culture.

A SUMMIT ALTAR?

That may have something to do with its height. Many mountain summits in the Greek world were places of sacrifice, but it is striking that most of the mountains where we have the best evidence for that, most often in the shape of enormous ash altars on the peaks, were relatively small by Greek standards: mountains like Mt Lykaion or Mt Arachnaion in the Peloponnese which were relatively accessible to the surrounding communities. In most of those sites the evidence for sacrifice (mainly in the form of burnt bone fragments and broken pottery) comes above all from the archaic period (8th-6th centuries BCE), and in some cases even further back into the Mycenean period.

On Olympus the pattern is quite different. Solinus (Polyhistor 8.6.) writing probably from the third century CE, talks about an altar on the summit, and tells us that offerings left there are found again undisturbed a year later. But there is no evidence at all for sacrifice on the highest summit, Mytikas. That’s maybe not surprising. It would have been perfectly possible to get goats or sheep up there—when I climbed it with friends a few years ago a dog from the refuge lower down the mountain followed us all the way up over the cliffs to the summit—but it’s not an obvious place for an altar: there isn’t much flat ground.

Instead the crucial evidence—really very little of it—was found on the southern peak of St Antonios between 1961 and 1965 during the building of a meteorological station: ash, bone fragments, fragments of pottery, two bronze statue-bases, three inscriptions to the god Zeus Olympios, and a set of coins, some of them Hellenistic, but most of them dating from the fourth or fifth century AD. Remarkably it seems that the summit was visited most of all in late antiquity, well after the christianisation of the Roman Empire had begun. There’s not much sign of anyone going up Olympus in the archaic period when the Homeric epics were composed.

OLYMPUS IN 19TH-CENTURY TRAVEL WRITING

Oddly that neglect is replicated in the mountain’s modern history. Olympus wasn’t on the standard 18th– and 19th-century travellers’ circuit, and that was partly because many northern European travellers from that period were following the ancient travel writer Pausanias, whose work doesn’t stretch to northern Greece, and who was interested primarily in those mountains that had shrines and statues stretching back to classical and archaic Greece.

The geographer and traveller Henry Fanshawe Tozer gives an account of climbing the mountain in the 1870s: he reached the lower peak of Profitis Elias, with its summit chapel, but his porters refused to go further because of the cold. He admires the view from the summit not just for aesthetic reasons but because of the way in which it gives him a glimpse of some of the landmarks of ancient history:

at our feet was the entrance of the deep defile forming the pass of Petra, through which Xerxes entered Greece, with yawning chasms and impassable precipices descending towards it, the ‘barrier crags of precipitous Olympus’ of the Orphic poet of the Argonautica…Athos rose majestic above all. A magnificent view indeed it was, together with the wide expanse of sea, which on this day was in colour a delicate soft blue…The heights on which we were standing were no unworthy position for the seat of the gods. [1]

But Tozer was very unusual in even attempting the journey.

BANDITS

The other factor was the way in which Olympus was associated with bandits. The complexity of the mountain made it an ideal stronghold for the klephts during the struggle for Greek independence in the 1820s and 1830s, and then again for robbers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

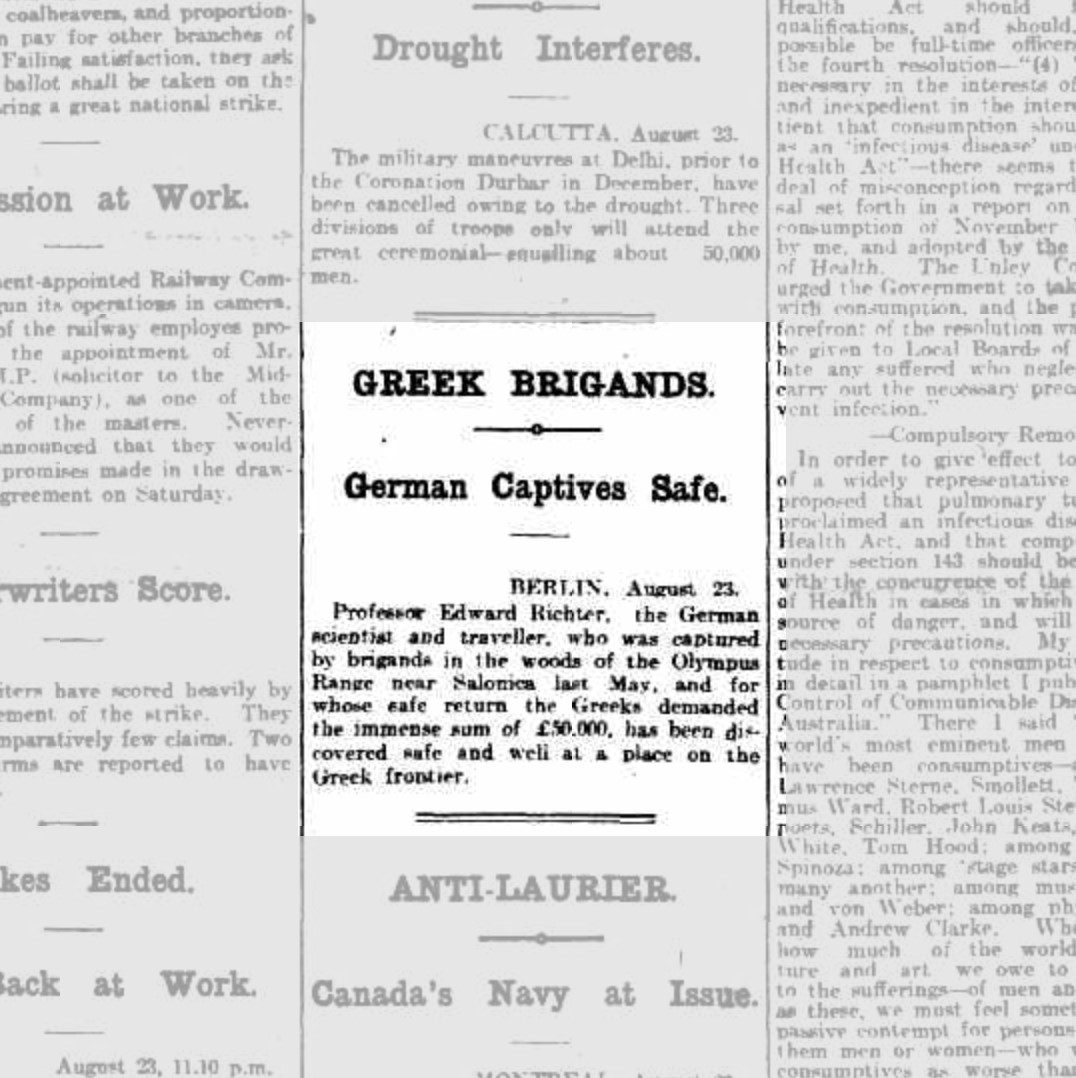

The German Edward Richter was kidnapped by bandits in 1911 in his attempt to reach the higher summits and the Ottoman guards travelling with him were killed.

The first recorded visit to the summit was remarkably late, in 1913. The second highest peak Stefani, with its dramatic cliffs, wasn’t climbed until 1921.

Today you can follow the paint splashes over the rocks to Mytikas, and it’s a relatively easy scramble, with no need for a rope, if you’ve got a head for heights. But it’s easy to see why it might be a daunting prospect if you’re looking over your shoulder for kidnappers.

CONCLUSION

I think it’s quite wrong to imagine that the mountains of the ancient Mediterranean were viewed simply as wilderness spaces. Instead, ancient viewers were fascinated precisely by the tension between mountains as places of human culture and mountains as places beyond human control and human knowledge. That contradiction is surely one of the key ingredients in the fascination we feel for mountains in the modern world too.

Today Olympus is a place of tourism much more than most other Mediterranean mountains—in summer it is crowded with trekkers going up to the summit. Until the second half of the twentieth century, by contrast, it was an enigmatic, inaccessible place, more so than most of the other mountains of mainland Greece—but for all that still marked by a story of human presence.

[1] Henry Fanshawe Tozer, Researches in the Highlands of Turkey, London, 1896: 220-21.

Illustrations: Mytikas summit from the Agapitos refuge; View from the Mytikas summit; page from Adelaide Evening Journal, 24 August 1911.