Jason explores the nature of environmental attitudes in antiquity.

How do ancient Greek and Roman attitudes to the environment relate to our own?

There has been a tendency to answer that question in very sweeping terms. In some cases, Greek and Roman culture are viewed as the starting-points for modern willingness to exploit the environment for human purposes. In other cases they are taken in exactly opposite terms as examples of environmental respect which was lost, according to one influential narrative, with the advent of early Christianity’s more anthropocentric approach to the natural world. One of the most influential statements of that view is a very short (five-page) article by Lynn White Jr published in the journal Science in 1967. Whatever you think of White’s wider argument it is clear that his characterization of Greek and Roman thought is cursory and simplistic.

In Antiquity every tree, every spring, every stream, every hill had its own genius loci, its guardian spirit. These spirits were accessible to men, but were very unlike men; centaurs, fauns, and mermaids show their ambivalence. Before one cut a tree, mined a mountain, or dammed a brook, it was important to placate the spirit in charge of that particular situation, and to keep it placated.

Certainly my first reaction to the article, as a classicist, was to be surprised that it could have quite so much influence despite being so sketchy.

WILDERNESS OR RESOURCE?

Mountains had a distinctive, but also complex place in ancient environmental thinking: often we find different views about how they should be treated side by side with each other even within a single text. They were viewed in some cases as wilderness places, as well as being associated with divine presence (as White makes clear); in some cases they had their own sacred spaces associated with worship of the gods. Many classical texts famously attack the Persian commander Xerxes for cutting a canal through the base of Mt Athos, presenting that as an act of hybris and offence against divine order.

But that association between mountain and inviolable wilderness was far less clear-cut than many modern characterisations have suggested. Mountains were also places of economic productivity, associated with and fought over by neighbouring cities, exploited by charcoal burners and wood cutters and by local communities in need of pasture land. How far their practice was sustainable in the modern sense is very hard to judge, but some have wanted to see the Roman Empire especially as a time of deforestation and environmental degradation.

DIO OF PRUSA AS ECOTOURIST

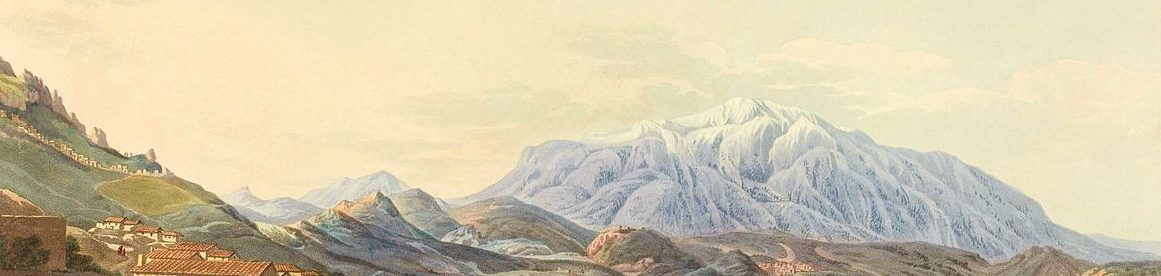

One of the most fascinating explorations of that range of possibilities comes in a work known as the Euboian Oration or Euboicus of Dio Chrysostom, a Greek orator and philosopher from Prusa in Asia Minor who was active in the late first and early second century CE. The work starts with a shipwreck scene on the island of Euboia (modern Evia: you can see the mountains off to the east as you drive south from along the coastline to Athens from northern Greece.)

Dio is rescued by a huntsman who offers him hospitality in his small community up in the mountains. Dio goes out of his way to characterise the hunters in positive terms. He admires their self-sufficiency, and their closeness to the mountain landscape they inhabit. The hunter explains that he lives with a friend, that each is married to the sister of the other, and that they have sons and daughters. Their fathers used to work for a rich man, grazing his flocks of horses, cows and sheep in the plains in the winter. Astonishingly this is one of only two surviving ancient descriptions of transhumance: the practice of moving livestock between summer and winter grazing. When the rich man died, his cattle were confiscated, but the hunters’ fathers stayed in the huts they had built as their summer base and turned to hunting. Dio gives an idealised account of their self-sufficiency and their satisfaction with a life close to nature (which clearly influenced Longus’ second-century pastoral novel, Daphnis and Chloe). The hunters feast with Dio on rich but simple food, including chestnuts and medlars and other fruits which have presumably been gathered from the wild, rather than cultivated. Dio is the original ecotourist.

MOUNTAINS AND THE CITY

And yet the text also makes clear that this fantasy of a mountain space removed from the economic frameworks of the Roman empire will not stand up to scrutiny. Later the hunter tells Dio about his recent visit to the city. It turns out he has been only twice in his life, the first time as a child with his father, and then the second time when a man came to their dwelling demanding money. The hunter tells Dio that he followed the man willingly into the city, presumably the city of Karystos, which stands at the very southern end of Euboia, beneath the slopes of Mt Ochi.

On arrival he is brought in front of the city’s assembly and accused—much to his bewilderment—of appropriating public land:

They have built many houses and they have planted vines, and they have many other advantages despite the fact that they have paid nothing to anyone for the land, nor have they received it as a gift from the people.

The underlying assumption here is that the mountains are the property of the city, to be administered by the city, and probably in law that was correct. Standardly there was a division, in Greek cities, between three different categories of productive land beyond the city—cultivated land, grazing land and woodland (with sacred space as a fourth)—each of which had its own dedicated laws and officials. Outside those spaces was the category of wilderness, which is what the hunter and his family occupy, but cities often asserted their sovereignty over wilderness too, given the valuable resources it could contain.

Even the second speaker, who speaks in the hunter’s defence, seems unable to break away from a viewpoint that has economic productivity as its ultimate goal:

I too own many acres, as I think some others do also, not only in the mountains but also in the plains. If anyone were willing to farm them I would not only give them for free, but would gladly offer them money in addition. For it is clear that they are of more value to me like that, and land which is inhabited and under cultivation is a pleasant sight, whereas wilderness is not only a useless possession to its owners, but also very pitiable, and a sign of the misfortune of its owners…So let them have it for free for the first ten years, and after that let them pay by agreement a small contribution from their produce, but nothing from their cattle.

It is as if Dio is telling us that his fantasy of mountain self-sufficiency is precisely that—an impossible dream that cannot possibly be maintained in the face of the economic realities of the Roman empire.

Illustrations: North coasts of central Evia panorama, C. Messier, CC0 1.0; Karystos, public domain.