Dawn reports on a project trip to an international mountain studies conference in the snow-covered mountains of Banff National Park, Canada: it’s a hard life being a mountain historian.

Just last week, the mountains in ancient literature and culture project team had the pleasure and privilege of attending Thinking Mountains 2018, a four-day interdisciplinary summit in mountain studies. Of course, such an event couldn’t happen just anywhere: it was based at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, right in the midst of the Canadian Rockies. The conference opened with what the organisers swiftly termed ‘the snowpocalypse’, with 40cm of unseasonal October snowfall settling in the course of just a few hours. This made for a particularly eventful journey for Jason, whose bus from Calgary airport perfectly coincided with 7-hour long delays on the Trans-Canada Highway. (I had travelled in the day before, and felt ever so slightly guilty as I enjoyed the Banff Upper Hot Springs watching the troublesome snow come down).

Thinking Mountains is one of the many excellent results of the Mountain Research & Initiatives centre at the University of Alberta. Among other things, they also run a MOOC (massive open online course) titled ‘Mountains 101’, offering a 12-week overview covering everything from the geological development of mountains to their modern-day cultural impact. The 2018 meeting marked the third instance of Thinking Mountains: I attended the second summit, in 2015, mid-way through my doctorate, and to say it changed the course of my PhD would not be an understatement. Why? Because it offered me the first chance to stop trying to explain to historians of other subjects why mountains mattered, and instead to get feedback from an audience full of people studying mountains on why (or if) my particular historical perspective on them mattered. (In terms of memorability, it also helped that the 2015 meeting was in Jasper, another beautiful spot in the Rockies, and featured my first ever experience of walking on a glacier).

During my interview for the postdoctoral fellowship with the mountains project here in Classics at St Andrews, I flagged Thinking Mountains 2018 as something I specifically wanted to do if I were to get the position: I wondered from the outset what the anthropologists, sports scientists, and mountaineering historians I had met in 2015 would make of classical mountains. We were fortunate enough to be allocated a full panel session just to our project, enabling us to spend 45 minutes going into the details of our project and sharing a few case studies, and then giving over the final 45 minutes to general discussion and feedback. This was led by our three ’roundtable’ members, Carolin Roeder, who works on modern Alpinism from a transnational perspective, Dan Hooley, who works on classics and classical reception, and Sean Ireton, who is currently co-editing (with Caroline Schaumann) a frankly excellently-titled book, Mountains and the German Mind: Translations from Gessner to Messner, 1541-2009. Their very astute comments were followed up by challenging questions and ideas from the wider audience. We left our session with a lot to think about.

Just as thought-provoking, however, was the rest of the conference, from the formal academic papers to the more laid-back evening events (this included an ‘evening of story and song’ with Sid Marty, an ex-park warden with plenty of eye-raising tales to tell about bears). When Thinking Mountains calls itself an ‘interdisciplinary’ summit, that isn’t just lip-service to the latest buzzword: it is what, at least from my perspective, the event is all about. ‘Mountains’, after all, can be studied from the point of view of geology, conservation, sport, film, history – and classics. Throughout the conference, different disciplines were challenged to think about how they ought to relate to each other within the field of mountain studies. We found ourselves challenged by the question of where our project fits in: which other disciplines should it be speaking to and, equally importantly, where do we draw the line in the sand regarding our own disciplinary distinctiveness? What is it about this project which gives it cross-disciplinary potential, and what is it about the approach of an early modernist and a classicist that gives it something unique?

Questions did not just swirl around the issue of disciplinary definition: both in our panel, and in several other papers which we attended, challenges were launched against terms such as ‘mountain literature’, ‘mountaineer’ and ‘mountaineering’. The latter two terms (and, frequently, the first as well) are all too often equated with the modern sport of mountaineering, and amidst debates about commercially-led expeditions the definition of ‘real’ mountaineering is constrained into ever narrower boundaries. If we expand these definitions – perhaps with a reversion to the pre-modern usage of referring to anyone dwelling on a mountain as a ‘mountaineer’ – would this make different stories, both present and past, more visible? Or, as one fellow mountain-thinker suggested, are these questions of definition really the most useful ones we can be asking? We hope to explore some of these questions in more depth – and other thoughts and ideas inspired by our week of Thinking Mountains! – in blog posts over the coming weeks and months.

Oh, and, of course – we climbed a (very small) mountain whilst we were there.

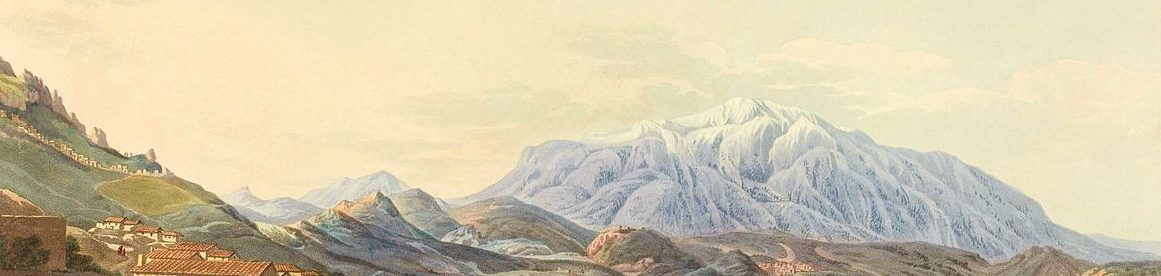

Illustrations: The view looking west from the Banff Centre, and on top of Tunnel Mountain (also known as Sacred Buffalo Guardian Mountain).