Dawn shares examples from early modern literature presenting mountains as spaces of isolation, and reflects on whether the future of mountain engagement might learn valuable lessons from the past.

In the middle of March, before the UK even went into lockdown, the Everest climbing season was cancelled. Base camp might be strangely empty this year, but just a few days ago China Mobile announced that they had installed 5G coverage on the mountain. Climbers in future years, when the mountain opens back up, will be better connected than most of the Scottish Highlands as high as 5,800m, if not higher: work is currently apace hauling networking equipment up to Advanced Base Camp at 6,500m.

Both this and the current crisis of infection and isolation put me in mind of Thomas Churchyard’s ‘discourse of Mountaynes’, included in his 1587 Worthines[s] of Wales. This poetic encomium lays out the numerous advantages offered by the mountain landscape. One standing atop a mountain may ‘Hath halfe a world, in compasse of his eye’, or can stoop to collect the ‘sweetest fruit in deede’. Most notably, however, the mountain stands above the valleys and apart from civilisation.

Churchyard first presents the mountain as an environment safe from physical infection:

[whilst] noysome smels, and savours breede below:

The Hill stands cleere, and cleane from filthie smell,

They find not so, that doth in Valley dwell.

[…] No ayre so pure, and wholesome as the Hill…

The concept of valleys or low places being subject to unhealthy miasmas, and of high places being correspondingly healthy and clean, was common in early modern Britain. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English travellers to Edinburgh, though they frequently had ripe comments to make regarding the Scottish character, were enchanted with the city built on a hill, and the corresponding purity of its air.

For Churchyard, the contrast between mountain and valley was marked not just in air quality but also in morality. The heavily-populated valleys were ‘A den of drosse, oft tymes more foule than fayre’, in which wealth bred strife, gluttony, pride, and ‘vice in every part’. By contrast, the mountains, though ‘poore and bare’, housed ‘more love… more happy days’ for the simple people who dwelt on their slopes. The seventeenth-century poet Charles Cotton expressed similar sentiments regarding his beloved Peak District home in ‘The Retirement’:

Farewell thou busie World, and may

We never meet again:

here I can eat, and sleep, and pray,

And do more good in one short day,

Than he who his whole Age out-wears

Upon thy most conspicuous theatres,

Where nought but Vice and Vanity do reign.

Cotton, instead of delighting in worldly pleasures, sings to his ‘beloved Rocks! that rise / To awe the Earth, and brave the Skies’. He ends his poem with a plea for, well, self-isolation: ‘Lord! would men let me alone… in this desart place, / Which most men by their voice disgrace’. Thus, within a landscape that only a few people truly appreciated, he might ‘Contented live, and then contented die’.

Cotton’s closing lines capture the ongoing paradox of the mountain environment: these far-above, far-apart spaces can only retain the qualities that make them beloved if relatively few people frequent them. It is far from novel to declare that Everest, for example, is no longer the place it once was, that its lofty removal from the world is the very thing being threatened – if not already destroyed – by the hordes of visitors that its ‘wildness’ attracts. The desire to experience a landscape for oneself, when held by too many people, threatens to destroy the qualities which make it worth experiencing.

Enter coronavirus, one of the strangest responses to environmental emergency that any of us could have imagined. With flights grounded, carbon dioxide levels are falling, and observers say that Mount Everest is experiencing a much-needed ‘detox’. There are no guarantees that once restrictions are lifted we won’t all go back to our bad old, environmentally-damaging ways, but I hope not. At the very least, lockdown has resulted in an awful lot of meetings and conferences that might otherwise have necessitated travel – between cities, countries, and continents – taking place in virtual space instead. Will organisations and individuals be quite so keen to dedicate time, money, and carbon emissions to in-person gatherings that could take place through the click of a few buttons instead? Probably not, and the benefit to the environment does come with the need to accept the loss of things we previously took for granted – I know that I for one have certainly enjoyed the ‘excuse’ that academic conferences have offered to visit parts of the world I otherwise wouldn’t have seen.

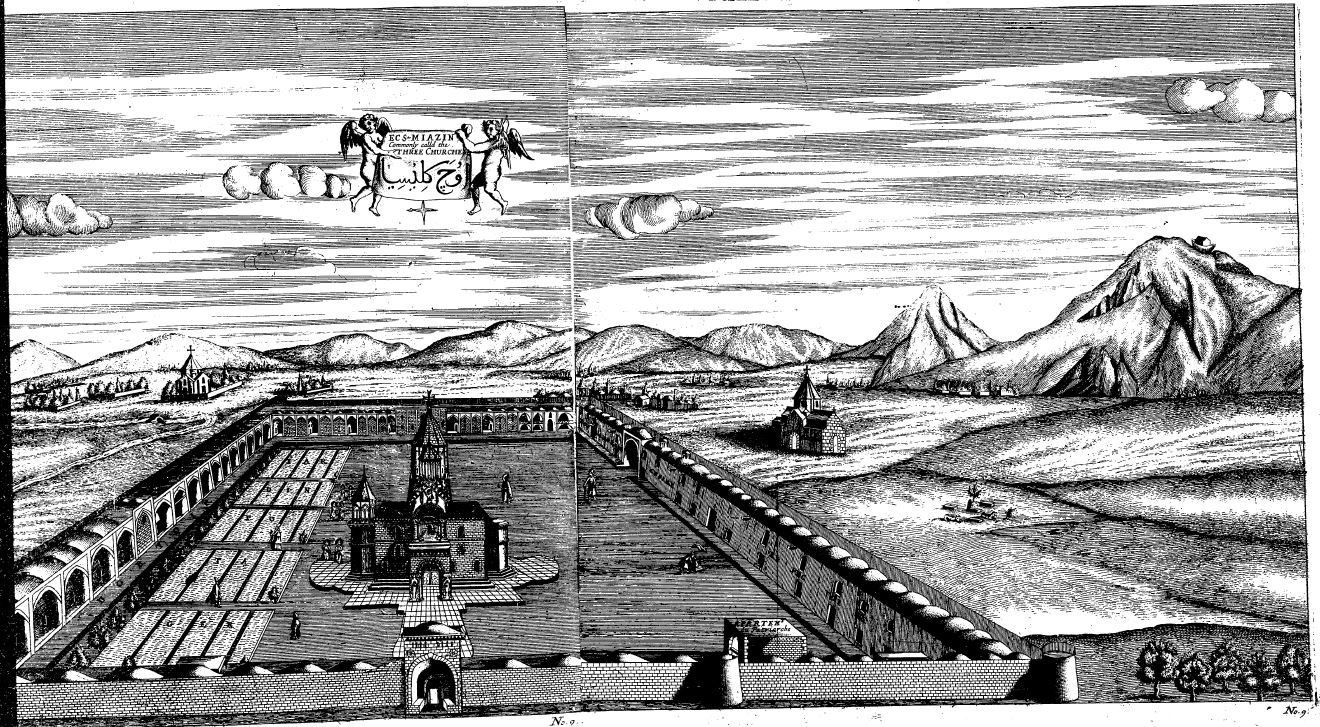

I wonder whether we need to accept similar change, and similar loss, in how we expect to engage with fragile landscapes such as the mountains – particularly those that require long-distance travel. In the period I focus on (1500-1700), mountain tourism didn’t exist in the form it does now, not because people weren’t interested in visiting mountains, but because the travel required to explore the landscape in the way we do now was accessible to a far narrower slice of the overall population. In the same period, however, published travel narratives abounded, with lavish descriptions and detailed woodcuts standing in for being able to experience a foreign landscape for oneself. Today, despite the far greater potential for photographs and videos to virtually ‘transport’ people around the world, we still want to go to remote, untouched landscapes, to touch them for ourselves and fill them up with our physical presence. Which is precisely how somewhere like Everest Base Camp has come to represent the very opposite of ideal ‘mountain space’. The last place to isolate either from physical infection or from the distractions of civilisation.

Of course, it’s very easy to say that, once travel is once again permitted, we should look at the mountain landscape but not touch it, that we should read about remote places but not visit them. Indeed, for many people it would likely be a much harder sacrifice than giving up on international conferences and in-person business meetings. That said, many changes that seemed unimaginable a few months ago have now taken place. Moreover, whilst complete self-denial is an extreme ‘option’, history demonstrates that our current mode of landscape engagement is extreme in its own way. It might also hold the potential to provide insights into alternative modes for ‘experiencing’ and appreciating mountain scenery.

Illustrations: Mount Everest from Gokyo Ri by phobus, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Portion of a fold-out plate from The Travels of John Chardin into Persia and the East-Indies (1686).