Jason explores the long history of representing the mountains around Thermopylae in both ancient and modern texts.

I have just been reading William’s Golding’s essay ‘The Hot Gates’, published in 1965 (that title translates the Greek name Thermopylae). It has made me want to go back and look a lot more closely at some of the ancient writing on Thermopylae as a site of conflict. Thermopylae has been the site of many battles both in antiquity and in subsequent centuries, most recently in 1941, when Allied Forces defended a position there against advancing German forces before withdrawing to the south. But what Golding is interested in, and what most modern readers and tourists have heard of, is the first battle there, in 480 BCE, between a tiny Greek force and the huge invading Persian army.

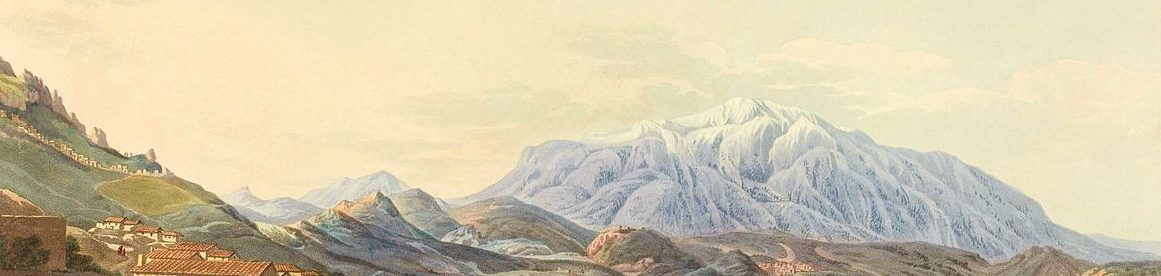

The story of that original battle is in part a story about the mountain that stands above Thermopylae. The famous image is of the stand of Leonidas and his 300 Spartans holding off the vast force of the Persians down at sea level, in the narrow neck of land with the sea on one side and the cliffs on the other. But the decisive act came at a much higher altitude, when a detachment of Persians finally made their way over a pass through the mountains, the Anopaia path over Mt Kallidromos, guided by the Greek Ephialtes: they brushed aside the Phocian troops stationed there to defend it, and outflanked the Spartans, attacking them from behind. That Persian victory was won by their control over mountain territory, achieved in this case through their access to local knowledge.

That theme of control and loss of control in the mountains is a very common one in ancient historiography: mountain territories are typically very difficult to interpret; those generals who succeed tend to be represented as exceptional figures. And yet the real glory in this battle is usually ascribed to the Greeks. The Persian manoeuvre, for all its success, is represented by Herodotus and others as one in a series of hybristic and ultimately self-destructive attempts to dominate the landscape. By contrast it is Leonidas’s resistance which is most often celebrated: almost as though the pass down at sea-level is viewed by later writers and tourists as more hostile, more heroic, in a sense more mountainous terrain than the gentle path taken by the Persians up above. I have only realised recently that for a long time, before I read Herodotus closely as an undergraduate, my mental image was of the Greeks holding a narrow pass at high altitude.

Certainly the valley of the river Asopos through which the Persians passed is an unusual place. The historian A.R. Burn wrote two remarkable short articles in the 1950s on high-altitude routes in the Greek mountains which have been used repeatedly in both ancient and modern warfare to move large bodies of soldiers quickly and secretly. He describes the valley as follows:

The upper Asopos valley runs along the top of the Anopaia or Kallidromos mountain, with the ridge of Liathitsa rising in gentle, grassy slopes on its north or right bank, and a lower parallel ridge, rising only just enough to make the place a valley at all, on the south. Between the two runs the valley, a furlong wide, flat-bottomed, full of silt, a couple of miles long (with a kink half-way, where you walk round the corner of the steep rocks of Liathitsa summit); so nearly level from end to end that the stream has cut itself deep meanders as though in an English meadow; and in April, when the snow is just melting, so full of white and purple crocuses that it is impossible to walk otherwise than on them. (Burn, ‘Helikon in history’ 315.)

I felt when I went there that I had entered a space which was strangely protected from the heat and ruggedness of the cliffs below.

There are wild horses and wide stretches of meadow. It feels, oddly, less mountainous and more benign, despite being higher. In that sense at least it is less suited to the notions of heroism within a rough landscape which are so familiar from ancient historiography and from modern writing about mountains too.

William Golding never made it up there. ‘The Hot Gates’ is a brilliant account of the mismatch between ancient evidence and modern landscape, and of the power of the imagination to overcome it. The mismatch is notoriously acute for Thermopylae, where the coastline has receded so far to the north that the narrow pass between cliffs and sea is now very hard to envisage. Golding sets out to follow the Persians upwards, but finds he cannot do it:

I moved back and peered up at the cliffs. The traitor had led a Persian force over those cliffs at night, so that with day they would appear in the rear of the seven thousand in the pass. For years I had promised myself that I would follow that track….I set myself to climb. The cliffs had a brutal grandeur. They were unexpectedly plainless and looked little like the smooth contours I had pored over on the map…I clambered up a slope between thorn bushes that bore glossy leaves. Their scent was pungent and strange. I found myself in a jumble of rocks cemented with thin soil…The blinding sea, the snow mountains of Euboea were at my back, and the cliffs leaned out over me. I began to grope and slither down again…So much for the map, pored over in the lamplight of an English winter. I was not very high up, but I was high enough. I stayed there, clinging to a rock until the fierce hardness of its surface close to my eye had become familiar. Suddenly, the years and the reading fused with the thing. I was clinging to Greece herself. Obscurely, and in part, I understood what it had meant to Leonidas when he looked up at these cliffs in the dawn light and saw that their fledgling of pines was not thick enough to hide the glitter of arms.

In the end, Golding’s imagination stays below with Leonidas. He gains inspiration here from the physical reality of Greece as so many other nineteenth- and twentieth-century travellers had before him: from the rough beauty of the rocks and cliffs which you can reach out and touch, or as he puts it ‘by the double power of the imagination and the touch of the rock’. This moment of epiphany involves an understanding of Leonidas’ motivation: his desire to make a plea, by the manner of his defence and his death, for unity among the Greeks in their defence of Greece—this ‘real’ Greece that Golding can still reach out and touch. In that sense he portrays Leonidas as a figure rooted, as Golding temporarily is himself, in the landscape, and Thermopylae itself as a battle played out within the rocks and mountains: not perhaps in the way he had anticipated, as an event decided by the easy movement of the Persians over that path across the summit, which seems so accessible when you look at a map and try to imagine it, but rather as a more claustrophobic experience, fought out within a space of struggle, hemmed in by the ‘brutal grandeur’ of the cliffs. To be in the mountains in Greece, on that view, you don’t always need to be very high. Golding puts Leonidas, rather than the Persians, in the long line of military heroes celebrated in ancient historiography for their hard-won mastery over mountainous terrain.