Dawn explores some early modern images of the classical story of Atlas’ mountainous metamorphosis.

I’m currently working on a book proposal (on, you’ll be surprised to hear, mountains in early modernity…), which includes the optimistic selection of the images which, in a world free from printing expenses and copyright concerns, I would ideally see illustrating the finished book. This has meant revisiting a chunky PDF file which I put together several years ago, collecting every image I could find dating from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries and which responded to the keyword ‘mountain’.

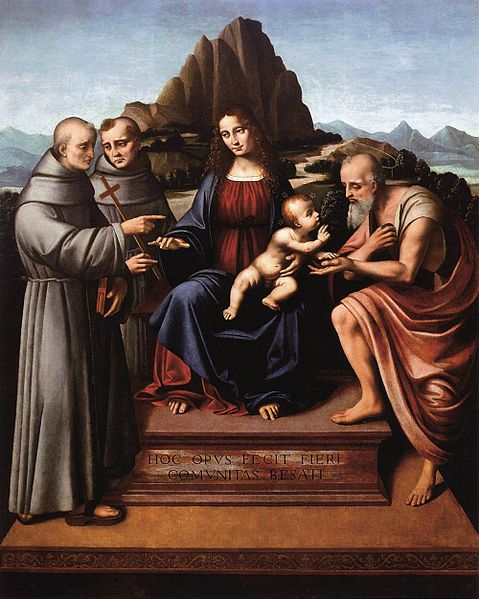

This entirely non-exhaustive search produced some 300+ images, with mountains depicted in illuminated manuscripts, in oil paintings, on tapestries, and in printed woodcuts or engravings: the artists of the early modern period, regardless of media, certainly did not ignore mountains as an important visual element of the environment and as objects rich in symbolic potential. Mountains also appear in a range of different visual roles, for lack of a better word: in some images, they dominate, whilst in others they offer a background of greater or lesser prominence. Certain patterns are also apparent: strikingly, mountains frequently feature in the backdrop of paintings of the Virgin and Child. In one of my personal favourites, Marco d’Oggiono’s Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints (c.1524), a more naturalistic backdrop of blue, distant hills is overwhelmed by a stylised, craggy peak in the middle distances, which frames and even seems to ‘throne’ the holy pair. The religious significance of mountains is an important theme in my research, and their ubiquity in devotional images is an issue I hope to explore further in the future.

Less frequent in my pool of images, but no less compelling, is the depiction of mountains in classical contexts. One particular motif which seems to have attracted printmakers of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is the story of Atlas being transformed into a mountain, as told by Ovid in Metamorphoses 4. Atlas, a being ‘vaster than the race of man’, enjoys a realm in the far west, covered by ‘a thousand flocks, a thousand herds’, and containing an orchard full of trees bearing apples of pure gold. He is jealously protective of these apples, having been warned by an oracle that one day ‘a son of Jupiter’ will come to visit him, and that same day his orchard will be stripped of its fruit. When Perseus appears, bragging of his divine parent and asking for a place to rest, Atlas immediately refuses and seeks to drive Perseus out of his lands. In response, Perseus turned his head away, and presented to Atlas the head of Medusa, which caused the famous transformation:

Atlas, huge and vast, becomes a mountain—His great beard and hair are forests, and his shoulders and his hands mountainous ridges, and his head the top of a high peak;—his bones are changed to rocks. Augmented on all sides, enormous height attains his growth; for so ordained it, ye, O mighty Gods! who now the heavens’ expanse unnumbered stars, on him command to rest. (Metamorphoses 4.651, Brookes More).

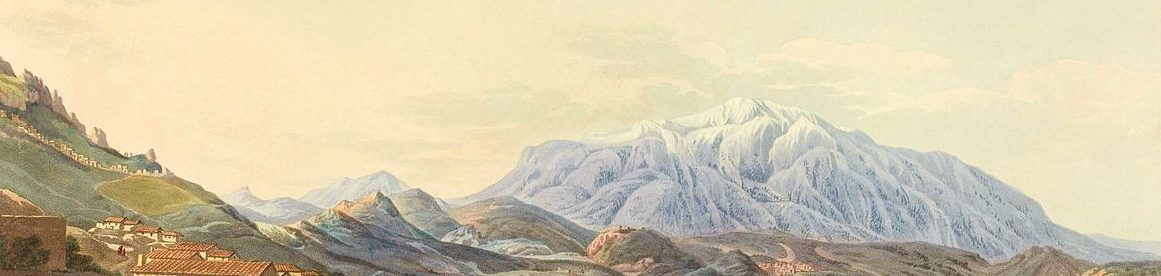

This moment marked the legendary origins of the rugged Atlas Mountains, a range stretching some 2,500km through the modern-day Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia.

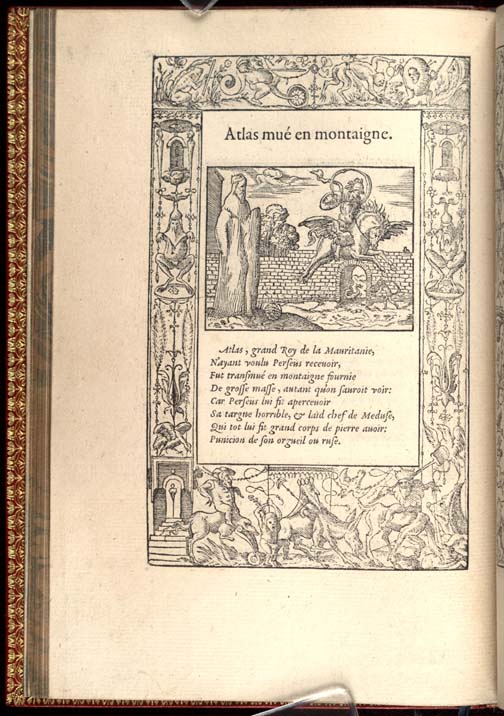

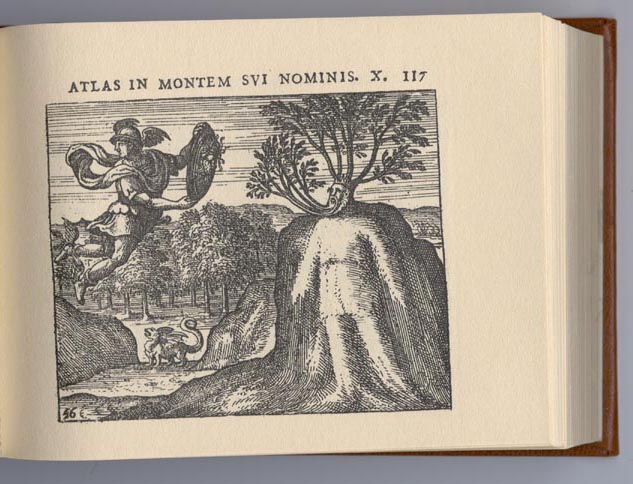

‘Picture books’ were as popular in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as they are today, and one of the most-frequently illustrated of all the classical texts was Ovid’s Metamorphoses. (Images from and discussions of various such editions can be explored, with a little patience for somewhat historic websites, at Ovid Illustrated and The Ovid Project: Metamorphising the Metamorphoses). As decades of illustrations progressed, Atlas became progressively more giant and his mountain transformation more mountainous: a 1557 edition published in Lyon and engraved by Bernard Salomon, sees Atlas transformed into merely a relatively large crag; a 1591 Antwerp edition from the Plantin workshop shows a hillock with the shadow of the shape of a man, and a head sprouting tree branches.

By 1606, the Atlas entry into a series of engravings by Antonio Tempesta offers a greater sense of scale: a crowned Atlas is caught in an expression of horror, his arms and head still flesh but his robes already transformed into a starkly-planed mountainside. This Atlas seems vast, set amidst a wider, mountainous landscape of which he represents the heights, but Perseus (astride Pegasus) seems enormous too. My favourite Atlas print, by Johann Wilhelm Baur (c.1639), shows a far more dwarfed Perseus, standing at the foot of a hill into which an exasperated-looking Atlas appears to be sinking, the lines of his flowing hair giving way to the etched lines of the upper slopes of the mountain, and his right foot already vanishing into the contours of the mountain’s base. This particular image of Atlas proved to be an enduring one: Baur’s design was re-engraved by Abraham Aubry (died c.1684), and the subsequent plates were re-used as late as 1703.

I must admit I’m not yet sure what to ‘do with’ these images in terms of drawing any great conclusions regarding the visualisation of mountains in early modernity. I certainly don’t want to fall into any simplistic or stereotyped discussion of the increasing ‘realism’ of mountain depictions as the centuries passed (not least because ‘realism’ seems somewhat ironic when considering an image of a giant turned into a mountain by the head of a gorgon). What I find fascinating about all of the images, however, is the choices made by the artists, within the constraints of their media, about how to depict this compelling moment of transformation, of the disturbing overlap of man with mountain. Do you have branches growing from Atlas’ beard, or the ripples of fabric harshening to sharp cliff-edges? Does Atlas’ form become that of the mountain, or does the mountain absorb his form?

Although Atlas’ transformation into a mountain marked just one of many metamorphic illustrations, and should be read within the wider context of the early modern fascination with Ovid, I also think it is emblematic of an important element of early modern thinking around mountains: namely, the extent to which they could either be anthropomorphised, or interpreted as analogous in their form and function to parts of the human body. However, the surprisingly talkative mountains of Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion (1612-22), or the peculiar seventeenth-century obsession with comparing mountains to (multiple, intimate) elements of the human physiognomy, must remain stories for future blog posts.

Illustrations: Marco d’Oggiono, Virgin and Child Enthroned With Saint, c.1524, Museo Diocesano in Milan, Wikimedia Commons; Tola Akindipe, Atlas mountain range, CC BY-SA 4.0; Bernard Salomon, Atlas turned into a mountain, 1557, Ovid Illustrated; unknown, Atlas in the mountain of his name, 1591, Ovid Illustrated; Antonio Tempesta, Atlas Turned Into a Mountain, 1606, LACMA collections; and Johann Wilhelm Bauer, Atlas Is Turned into a Mountain by the Sight of Medusa’s Head, c. 1639, Harvard Art Collections.