Jason considers the merging of modern categories of the sublime and the picturesque with an appreciation of the classical past in the works and writings of Edward Dodwell (1767-1832).

A lot of my work on the project recently has been on ancient texts and contexts. One of the goals of that work is to recapture something of the sophistication of Greek and Roman engagement with mountains, as a way of challenging deep-rooted assumptions about the lack of interest in mountains before the mid 18th century.

The project also has another strand, however, which involves looking at the influence and afterlife of classical engagement with mountains. One of our hypotheses is that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century responses are often much more rooted in classical precedents than the standard narrative acknowledges

Travellers’ accounts from Greece and Italy from that period are a particularly interesting place to look. Many of them draw heavily on the aesthetic vocabulary that was so popular in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Greece in particular was an important focus for the development of thinking about landscape: the Napoleonic wars had made the traditional Grand Tour destinations of western Europe inaccessible in the early 1800s, and attention turned more and more to Greece and western Turkey. At the same time many of these authors were steeped in ancient literature, especially authors like Strabo and Pausanias.

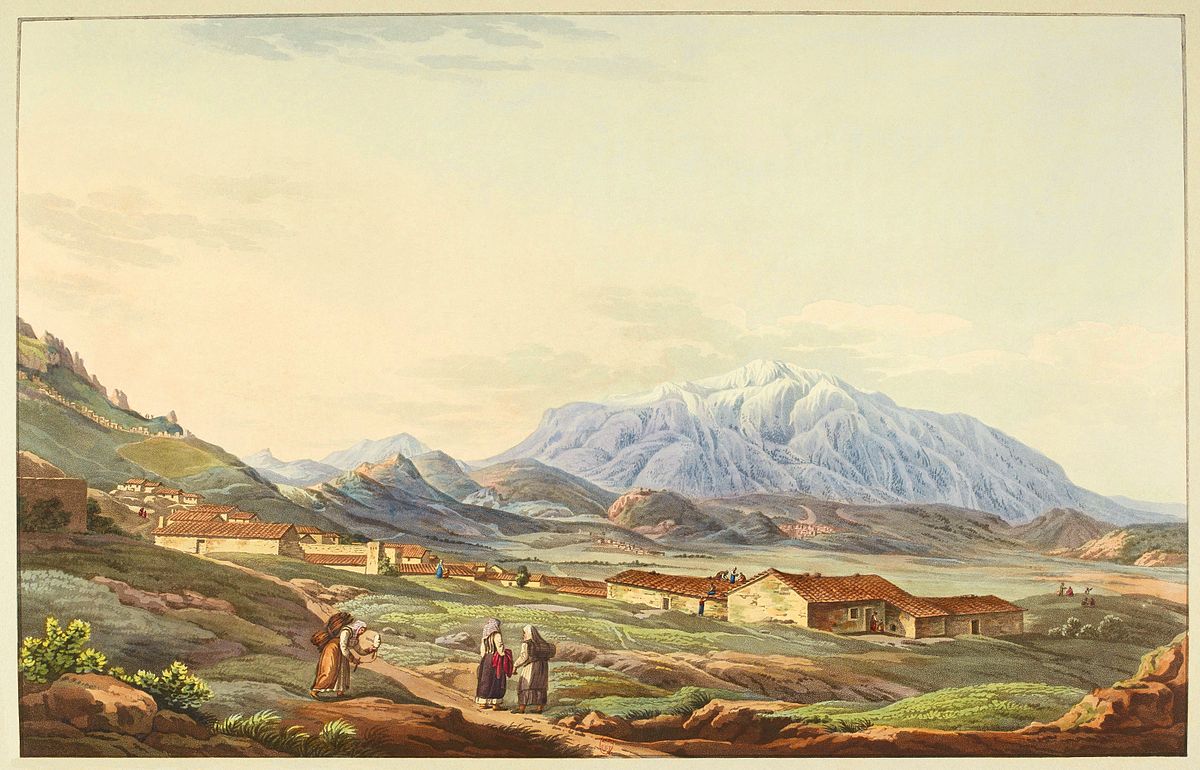

One of my favourite examples is Edward Dodwell. Dodwell’s journeys through Greece took place in the first decade of the nineteenth century, but he waited until 1819 to publish them, with the title Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece during the years 1801, 1805, and 1806. Dodwell was an artist (his work was heavily dependent on the use of a camera obscura). Many of his paintings from those trips involve views of mountains or views from mountain summits.

One of the striking things about his descriptions of landscape is that they often combine aesthetic judgements—including the language of the beautiful, the picturesque, the sublime—with a celebration of the classical heritage, as if the two are inextricably linked in his mind.

On a hill near Missolonghi in north-west Greece, for example, he says that ‘we were deeply impressed by the view which it displayed. The features are truly beautiful; and the objects are rich in classical interest’. At Thermopylae ‘the beauty of the scenery was illuminated by many reflections from the lustre of the classic page’. Of Mt Ithome he says that ‘few places in Greece combine a more beautiful, and at the same time a more classical view’.

Dodwell’s account of climbing Mt Hymettos, just outside Athens, is a wonderful example (Volume I, pp. 483-94). He sets out, together with his collaborator Simone Pomardi, in the belief ‘that its summit would present one of the most extensive views in Greece’. They reach the monastery of Sirgiani, four and a half miles from the centre of Athens, in the evening, only to find it deserted with the doors shut. They climb the walls of the monastery ‘with a great deal of difficulty and some danger’. Inside they find that

a deep silence prevailed throughout the cells; the occupants of which seemed to have recently retired. The store-rooms were open, and well furnished with jars of Hymettian honey, ranged in neat order: next were large tubs of olives; and from the roof hung rows of grapes, pomegranates, and figs. The only inhabitants left in the convent were some cats, who seemed to welcome us in the absence of their masters. We took complete possession of the place, and feasted on the produce of the deserted mansion, which seemed to have been prepared for our reception.

In the morning, they ride to the summit, ‘over the bare and shining surface of the rocks’. The view surpasses even Dodwell’s elevated expectations:

I had already seen in Greece many surprising views of coasts and islands, and long chains of mountains rising one above another, and receding in uncertain lines, as far as the eye could reach: but no view can equal that from Hymettos, in rich magnificence, or in attractive charms. The spectator is sufficiently elevated to command the whole surrounding country, and at the same time not too much so for the full impression of picturesque variety; and I conceive, that few spots in the world combine so much interest of a classic kind, with so much harmony of outline.

As so often, aesthetic, painterly judgement (the ‘attractive charms’, the ‘picturesque variety’, the ‘harmony of outline’) is combined with antiquarianism. Even by Dodwell’s normal standards the catalogue of what can be seen from the summit is extraordinarily detailed, stretching for six whole pages. The pages preceding the arrival at the summit include extensive references to Ovid, Pliny the Elder, Pausanias and Plato. Up here they seem to be alone with the classical. The jars of Hymettian honey, which Hymettos had been famous for even in the ancient world, and which wait for them in such abundance in the monastery, seem to signal the fact that the the mountain is welcoming them into a place where antiquity is still alive in the present. They pass several more days drawing on the summit, and sleeping in the monastery, and then they go back down to Athens.

As usual, the painterly quality of this account is hard to parallel in any description of a mountain anywhere in classical literature. And yet in the case of Ovid at least Dodwell is keen to suggest that his ancient sources share his own sensitivity to landscape. He quotes from Ovid’s description of Mt Hymettos and its ‘purple hills’ (purpureos colles, Ars Amatoria 687), and then launches into a detailed justification of the accuracy of Ovid’s description:

Hymettos is remarkable for its purple tint, at a certain distance; particularly from Athens, about an hour before sun-set, when the purple is so strong, that an exact representation of it in a drawing, coloured from nature, has the appearance of exaggeration. The other Athenian mountains do not assume the same colour at any time of the day. Pentelikon, which is more distant, and covered with wood, is of a deep blue. Parnes, Korydallos, and the others, are variegated, but generally parched and yellow. It seems clear, that in speaking of the colles of Hymettos, Ovid had in view the number of round insulated hills at the foot of the mountain; which are particularly remarkable and numerous near Sirgiani.

That attention to colour and to shape ascribes to Ovid an artistic sensibility like Dodwell’s own. And the phrase ‘had in view’ asks us to imagine Ovid standing there for himself, as Dodwell himself clearly has, gazing down at the vista beneath him.

For Dodwell, in other words, his own very modern aesthetic sense is presented as something parallel with what he finds in classical sources, rather than as something separate and different and new.

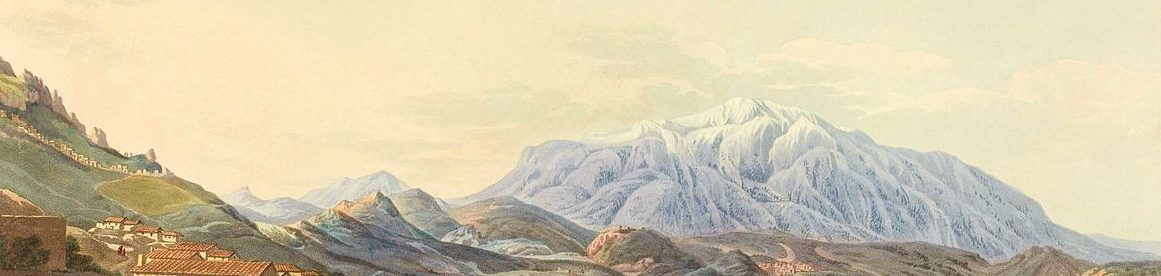

Illustrations: Edward Dodwell, ‘Mount Olympos, as seen between Larissa and Baba’, from Views in Greece (London: 1821), p. 99, and Dodwell, ‘Parnassus’, Views in Greece, p. 19.