Jason offers some final thoughts, and looks ahead.

Over the last few weeks we have been tying up some loose threads and bringing our mountains project to a close. We are enormously grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for their investment in the project over the last six years.

In the process it has been a pleasure to look back—but also to look forward to the future.

The project as we initially envisaged it had two main strands (but impossible to separately firmly): first, to look at the history and representation of mountains in premodern cultures, especially in the ancient Mediterranean and in early modern European culture; and second, to bring those histories more into dialogue with modern responses to mountains, both as a comparative exercise and by thinking about the underestimated influence of (e.g.) classical thinking about landscape on modern engagement with mountains.

One of our overarching goals, in both strands, was to challenge traditional narratives that still tend to see a split between what is widely interpreted as premodern indifference to mountains and modern obsession and fascination with mountains from the eighteenth century onwards.

Both of those strands have proven to be incredibly rich and productive. The results are published (or will be published soon) in the project’s three book publications, Mountain Dialogues (2021), The Folds of Olympus (2022) and Mountains Before Mountaineering (forthcoming 2024) (see here for a list of project publications). But lying behind those three volumes has been a huge amount of preliminary work—blog posts, conference and seminar papers, published chapters and articles, and most importantly a lot of conversations.

But the thing that strikes me most now in looking back is how all of that work has opened up so many new areas of study for the future—in many cases areas we would never have anticipated.

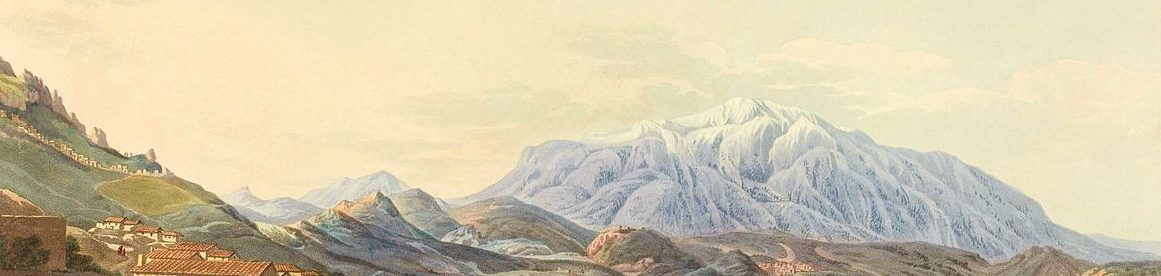

For one thing I’m very much aware that we have only scratched the surface of the long history of the mountains of Italy and Greece and the Mediterranean world more generally. For example, one key element of the project as originally envisaged was a series of publications on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century travel accounts from Greece and the eastern Mediterranean. Our hypothesis was that these would be particularly interesting texts for interrogating the importance of the classical tradition within modern thinking about mountains: many of these travellers’ accounts present themselves as very modern texts, not least because they are imbued with fashionable ideas about the sublime and the picturesque, but they are also at the same time shaped by Greek and Roman precedents and by the classical education of their authors.

(What is it like to be a classicist and someone who loves spending time in the mountains? How can we map out the range of ways in which individuals and communities have articulated the links or disjunctions between those two identities over the last millennium or more? I think there is a fascinating history waiting to be written on those questions. It would have to be quite a personal history for me…)

We have published among others on Patrick Brydone, Edward Daniel Clarke, Edward Dodwell, Christopher Wordsworth—but we have also realised more and more what a vast and largely untapped body of material this is both for the history of mountains and also more broadly. There is a lot more work to do.

My research on mountains in classical antiquity has also made me realise, more clearly than I had done in envisaging the project initially, how much there is still to do in understanding ancient patterns of representing landscape and human-environment relations and their relationship with their modern equivalents. Among other things I’m working on some publications now that aim to get to grips with that question for the Greek literature of the Roman empire, not just in relation to mountains but also more broadly. It’s exciting to be re-reading familiar texts and finding that they look a bit different in the light of modern approaches from ecocriticism and landscape studies.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the opportunities we have had for dialogue with others working on the history and representation of mountains across a wide range of different disciplines has made it clear to us that there is huge potential for interdisciplinary work in what we have called the ‘mountain humanities’. That has been an expanding area over the last decade or so, but a lot of research is still quite disparate and disconnected, focused within conventional academic disciplines without much dialogue across those boundaries. We hope that this project—not least through our final publication on possible futures and prospects for the mountain humanities—can make at least a contribution to generating new research and new ways of working in the field.