I have wondered for a long time now how it would be to write a book on the role of Classics in the history of mountaineering and mountain writing.

There are plenty of examples of mountain writers who have combined their climbing with an interest in Greek and Latin literature, from early modern authors like Petrarch and Pietro Bembo, through to the many travellers in Greece, Italy and Turkey in the 18th and 19th centuries who might not have seen themselves as mountaineers, but who nevertheless spent a lot of time climbing mountains side by side with their antiquarian interests in ancient history and archaeology.

The problem is that when you get to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that becomes the history of an absence. Many, even most British mountaineers from that period were classicists in some sense, either through having a basic literacy in Latin and Greek literature from their schooldays – Classics was of course central to elite, male education at the time – or in some cases through their studies at undergraduate level and beyond.

But you wouldn’t necessarily guess that from their writings. The mountains seem to be a space of physical recreation and physical challenge that is separate from, or at least parallel to their classical reading and scholarship, and you have to search very hard to find any mention at all of Greek and Roman literature in their descriptions of mountain experience.

Arguably that absence is important and interesting in itself, but it does make it a hard history to write.

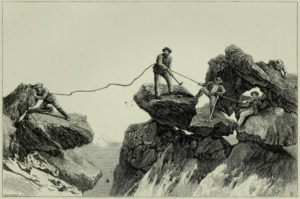

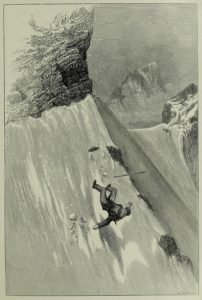

I have been intrigued, however, by one prominent exception, in Edmund Whymper’s Scrambles Amongst the Alps. Whymper’s book is probably the most famous work of 19th-century mountaineering writing: it culminates in an account of the Matterhorn disaster of 1865, where four of Whymper’s companions plummeted to their deaths on their way down after the first successful ascent to the summit. The book regularly includes quotations (in English translation) from various Greek and Latin authors (alongside various equivalents from English literature, for example from Shakespeare) as chapter epigrams.

That’s a particularly interesting example partly because Whymper himself was much less of a classicist than many of his British contemporaries: his educational level was relatively low by comparison with university men like Leslie Stephen (as Peter Hansen has shown here, the early membership of the Alpine Club, founded in 1857, ‘was drawn overwhelmingly from the professional middle classes’, although with some variation: more than half had had a university education, and just over one in three who had been to public schools, but that still left room for plenty of room for members not in either category).

There is not a hint of any classical learning anywhere else in Whymper’s text. As for many other mountain writers of this period, conventional university erudition seems to be displaced in favour of a history of peaks, first ascents, and the knowledge of mountain geology that often accompanied those things, in many cases detailed through scholarly footnotes and appendices.

That makes me want to know all the more what the function of these epigrams is in Whymper’s text.

One answer might be that he uses them as a way of guaranteeing his own membership of a literate elite, which he may have been more insecure about than other more highly educated mountain writers.

As far as I can tell, at least some of the quotations are taken from a collection called Beautiful Thoughts from Greek Authors, by Craufurd Tait Ramage, published in 1864, seven years before Whymper’s Scrambles (e.g., epigram to ch. 10: ‘how pleasant it is for him who is saved to remember his danger’; ch. 12: ‘A daring leader is a dangerous thing’—both from Euripides). Ramage’s book collects a series of short extracts from Greek authors, with no reference to their wider context, in many cases translated and presented in such a way as to make classical authors seem like contemporary exponents of Victorian moralising discourse. Certainly the use of this collection wouldn’t have required any particularly high level of classical knowledge on Whymper’s part.

That is not to say that the epigrams are just inert additions, tacked on to the main text for show. Among other things they back up Whymper’s interest in the way in which his text, and the practice of mountaineering more generally, exemplifies what he views as universally valued virtues: ‘the development of manliness, and the evolution, under combat with difficulties, of those noble qualities of human nature—courage, patience, endurance, and fortitude’ (p. 379, from the closing paragraphs of the book).

But in re-reading his work, I have been struck above all by the gap between the vague generalisations about human virtue in the epigrams and the precision of Whymper’s account in the chapters themselves—and in his accompanying drawings—with their very careful recall of exact actions and exact places in the mountains.

I think the possibility of mismatch between epigram and what follows is probably inherent in the very practice of using chapter epigrams like this. Presumably most authors choose epigrams because they think they are a good match, but they nevertheless always gain some of their force and fascination from the fact that there is an ever-present potential for incongruity. An epigram like this poses a question: how does the generalising pronouncement it contains measure up against the more complex representation of lived experience that follows? Can we make them fit?

One of Whymper’s epigrams even seems designed to acknowledge that difficulty (Chapter 20: ‘In almost every art, experience is worth more than precepts’, from Quintilian).

For me, reading this text now, these epigrams serve above all as a foil to remind me of what is special and compelling about Whymper’s writing—all the qualities which make me want to read his work again and again. In that sense for me they point to the tendency for mountain environments to be constructed as spaces beyond the sphere of traditional education—in other words more or less in line with what I have said above about the absence of classical references from classically educated mountain writers (although whether that is what Whymper would have intended is another matter…)

A fuller account would need to look much more closely at comparison points: what other mountain and adventure writing from the same period uses epigrams in similar terms? what is the history of use of Whymper’s source texts? is it clear why Whymper chose particular quotations for particular chapters? I haven’t done that work yet. If anyone can help with those questions I would love to know!